Casein is one kind of paint I haven't used. In years past I learned to handle oils, acrylics, watercolor, gouache, and pastel, but never wanted to try casein, which wasn't easily available anyway and which nobody used anymore. Casein is the protein fraction of milk and comprises most of the curds that result when milk is treated in various ways. For example, when rennet is added, the curds that result are made into cheese. Casein can also be used as glue, and as a vehicle for paint.

Casein has been used for paint for as long as there have been people--even some prehistoric paintings seem to contain it. Until the advent of acrylic paint in the mid-twentieth century, casein was a well-known and preferred paint among illustrators and some fine artists. Today only a few companies make and sell casein paint, notably the

Shiva brand, although Sinopia sells their "milk paint," which seems to be the same thing in a more liquid form, whereas the Shiva paint is stiffer and tubed.

Not long ago while searching for suitable grounds for metalpoint, I happened on

Artisanal Milk Paint

from Sinopia, the pigment company located in San Francisco. Although I

had visited the site in years past to buy bulk pigment, I hadn't been

there for a long while. I'd been told that Sinopia sells a casein-based silverpoint ground

that contains chalk, and I bought some to try out. But the intriguing

thing on the site these days is their milk paint--casein paint--in four ounce jars and various colors. This kind of paint is often marketed for decorative arts--painting furniture, indoor applications, crafts and the like. So it doesn't go by the kinds of names fine artists are used to like "cadmium yellow" and so on. Instead, these are named by the color, like indoor house paint for example, and the actual pigment isn't listed, in most cases. Nonetheless, casein has a reputation for sturdiness, utility, and relative ease of use. So on a whim I decided to try it out and ordered a few jars--black, a warm white, an ochre-like yellow, two blues, two reds and a pink.

The Artisanal Milk Paint labels say the ingredients are "water, casein, flax oil, pine resin,

fossilized sea shells, olive oil soap, beeswax, pigments, salt." They

don't list the pigment names. I opened one of the 4 oz jars at random to

find that the top is sealed. Pulling off the seal reveals a thick,

paint that's the consistency of somewhat thin honey or thick yogurt. According to the Sinopia site, this paint will last a long while if kept sealed, and even if it does form a surface skin, all you have to do is remove the solid part and the paint underneath will still be usable. Unfortunately, their "Charcoal Black" was almost completely livered in the container, while the "Dairy White" was considerably thinner than the other colors. This is actually casein-emulsion paint, or so it seems based on the ingredients list, which contains both an oil and casein plus a resin. So I wonder if the variable results have to do with pigment qualities or whether it has to do with the vehicle. The recipe is intriguing enough, but you can also make your own based on

several recipes on the Sinopia site. Casein can be made into paint by treatment with lime, borax, and ammonium carbonate, and recipes for each are given. They also sell casein and borax as powders.

My first impression of the paint is that it reminds me of the poster paint children use in school, but considerably thicker. You can thin it a bit with water, but I was cautious because of unfamiliarity with the material. The paint goes down

smoothly and has to be brushed out and covers pretty well, though a

thin layer looks semi-tranparent. As casein is supposed to do, in my hands it dries like lightning. It mixes okay--I tried a yellow and a pink to

make a "flesh" tone, which worked pretty well, and scrubbed it onto a piece of test material. The surface was dry in under five minutes. As I've learned to do with acrylic and gouache, I kept a small spray bottle handy to mist the paint, which was portioned out on a glass palette.

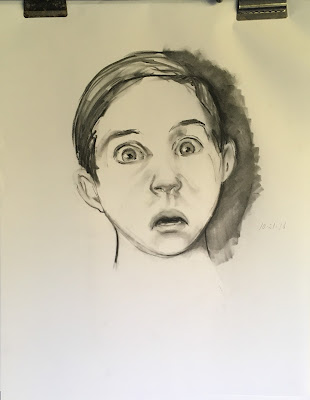

You can lay it on in fairly thick layers and it dries without cracking, though there's really no reason to put it on so thick. After it dried, I used the pink-yellow piece of scrap for a very quick sketch of a model skull using only black and white to make a range of values. With a big flat brush, and paying almost no attention to drawing and much more attention to masses of value, I roughed in the skull. This little sketch (about 8x10) was literally dry in five minutes. If I had chosen, I could have gone back and added any number of details with this paint, using smaller brushes.

|

| "Spinnaker," 2016 |

This is my second painting using this material. "Spinnaker" is 22x15 on illustration board. The reference was a magazine cover but I changed the sky and sails considerably. This was only an experiment with the paint, but it certainly demonstrates its capabilities. To make the painting I gridded up the reference and transferred it to the board in pencil, making a fairly detailed drawing. I used black, a dull red, a warm white, and a dull yellow. I was frustrated by the black paint being so livered, though it was usable enough in the tiny quantities I needed for this picture. The size was daunting too, but it gave me plenty of acreage for investigation of brushing, drying, and other properties of the paint. It takes perhaps two coats to achieve significant opacity with the white, and mixing isn't simple, but the result is certainly serviceable and the colors reproduce well in photos.

Based on experience with this material, I will probably buy some tubed casein paint one of these days to use in the future.

----

Casein paint and recipes:

Artisanal Milk Paint

Earth Pigments

Milkpaint

During the 1920s and 1930s

Post New Year covers featured the Leyendecker baby in an image reflecting or commenting

on the various political hopes and ideas that were current. The cover for

1928 for example featured the baby on a rainy wet day, under an umbrella, a veiled

reference to the election year, perhaps. Certainly the symbols of the

two political parties plus the baby aboard an ark suggest that some

believed that an enormous flood was coming. An alternative proposal is that the wet weather might symbolize the

hope for repeal of the dry time of Prohibition, which had plunged the country into

all sorts of difficulties during the 1920s.

During the 1920s and 1930s

Post New Year covers featured the Leyendecker baby in an image reflecting or commenting

on the various political hopes and ideas that were current. The cover for

1928 for example featured the baby on a rainy wet day, under an umbrella, a veiled

reference to the election year, perhaps. Certainly the symbols of the

two political parties plus the baby aboard an ark suggest that some

believed that an enormous flood was coming. An alternative proposal is that the wet weather might symbolize the

hope for repeal of the dry time of Prohibition, which had plunged the country into

all sorts of difficulties during the 1920s.  Mr. Leyendecker did more than 300 covers for the Post, and his last is memorable. It's the New Year cover for 1943, showing the baby in an Army helmet, swinging a rifle complete with bayonet. He's breaking apart the symbols of the Axis powers--the Nazi swastika, Japanese rising sun, and Italian fasces. The image could be considered hopeful rather than factual, given that when the cover was published the outcome of World War II was still in doubt.

Mr. Leyendecker did more than 300 covers for the Post, and his last is memorable. It's the New Year cover for 1943, showing the baby in an Army helmet, swinging a rifle complete with bayonet. He's breaking apart the symbols of the Axis powers--the Nazi swastika, Japanese rising sun, and Italian fasces. The image could be considered hopeful rather than factual, given that when the cover was published the outcome of World War II was still in doubt.