During the next several months there are likely to be dozens of opportunities for painting and drawing snow scenes. The watercolor above is an example of the kind of scene outside my studio during winter. I expect to do quite a few more sketches like this if the long range weather forecasts are even close to accurate.

A site for rumblings and ruminations about traditional oil painting, art, aesthetics, and the wider world of art. And for posting examples of my current and past work too. If you have an interest purchasing a work, or want to commission a portrait, or if you just want to talk about art, drop me an email at ghoff1946@gmail.com. All writing and original art on this site is copyright Gary L. Hoff, all rights reserved. All other images are copyright their respective owners.

Friday, November 29, 2019

Black Friday

During the next several months there are likely to be dozens of opportunities for painting and drawing snow scenes. The watercolor above is an example of the kind of scene outside my studio during winter. I expect to do quite a few more sketches like this if the long range weather forecasts are even close to accurate.

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Happy Thanksgiving

This week marks the American holiday of Thanksgiving. Our Thanksgiving holiday has been celebrated in various ways, many devoted to retelling the story of Pilgrims, their assistance by Native Americans, and a feast of thanks that they held. But the story isn't so simple.. It's a legal national holiday now, but only since around the middle of the last century. It is true that a holiday of thanksgiving has been held on a local and less formal basis off and on since before this country existed. The one we celebrate now actually has its roots in an attempt by President Abraham Lincoln to foster national unity during the terrible Civil War of the 1860s.

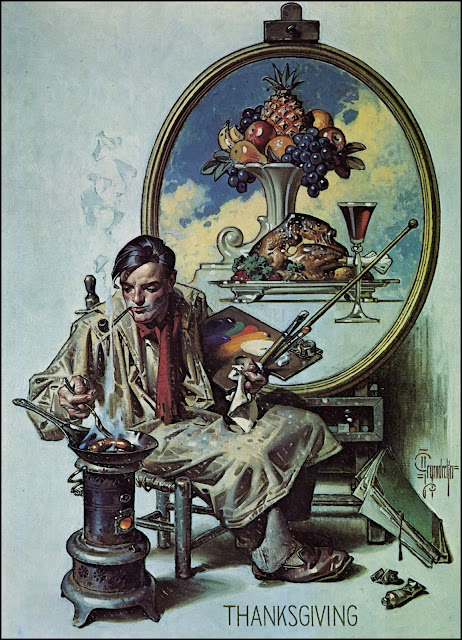

Our popular holiday is remains rooted, though, in Pilgrims and turkeys and feasting and of course football games. Popular illustrations of the holiday, beginning a century or more ago and continuing into our own century, still celebrate those Thanksgiving icons. These are a few of my favorites Thanksgiving illustrations from the golden age.

This magazine cover by J.C. Leyendecker for Thanksgiving 1928 exemplifies the golden age of magazine illustrations. Among the illustrators working during that time, Mr. Leyendecker was the most successful and famous. He did many magazine covers, advertising illustrations (the Arrow collar man), and was a role model for many who followed. Norman Rockwell was among those who counted him as a personal hero.

This one, also by Mr. Leyendecker, is a particular favorite of mine. It dates to Thanksgiving 1918, and gives us an American soldier leading (or being led by) a turkey. The first World War had ended a scant three weeks earlier amid delirious celebrations of thanksgiving. The metaphor of the image was obvious to everybody, worldwide.

Nearly three decades later, near the end of his career (1946) Mr. Leyendecker produced this cover art for the Thanksgiving issue of The American Weekly magazine. No football, no actual turkey, just a struggling artist dreaming of a feast.

This cover of The New Yorker from only a few years later is considerably more "cartoony" than anything Mr. Leyendecker ever did, but described the situation then and now.

Happy Thanksgiving

---

Similar posts:

Thankfulness

Thanksgiving Art

Our popular holiday is remains rooted, though, in Pilgrims and turkeys and feasting and of course football games. Popular illustrations of the holiday, beginning a century or more ago and continuing into our own century, still celebrate those Thanksgiving icons. These are a few of my favorites Thanksgiving illustrations from the golden age.

This magazine cover by J.C. Leyendecker for Thanksgiving 1928 exemplifies the golden age of magazine illustrations. Among the illustrators working during that time, Mr. Leyendecker was the most successful and famous. He did many magazine covers, advertising illustrations (the Arrow collar man), and was a role model for many who followed. Norman Rockwell was among those who counted him as a personal hero.

This one, also by Mr. Leyendecker, is a particular favorite of mine. It dates to Thanksgiving 1918, and gives us an American soldier leading (or being led by) a turkey. The first World War had ended a scant three weeks earlier amid delirious celebrations of thanksgiving. The metaphor of the image was obvious to everybody, worldwide.

Nearly three decades later, near the end of his career (1946) Mr. Leyendecker produced this cover art for the Thanksgiving issue of The American Weekly magazine. No football, no actual turkey, just a struggling artist dreaming of a feast.

This cover of The New Yorker from only a few years later is considerably more "cartoony" than anything Mr. Leyendecker ever did, but described the situation then and now.

Happy Thanksgiving

---

Similar posts:

Thankfulness

Thanksgiving Art

Friday, November 22, 2019

Drawings of Sculptures

|

| Unknown, "Portrait Bust." 1st Century CE |

Using those images is a simple way to enhance drawing skills, practice with a particular mediium (whether pencil, charcoal, conte or pixels), explore various techniques, and study how the ancients produced their works, among any number of other reasons. I've been working with some of these kinds of busts and figures, particularly the often-admired portrait busts from the time of the Roman Republic. These are unlike busts from the later Empire when many many images of Augustus Caesar, to name only one emperor, flooded the world. Many of those are unique and very personal in the sense that they are single copy images of the person who commissioned them, or one of his relatives. These portrait busts explore what seem to us as realistic renderings of a person. Yet these realistic portraits were actually deliberately accentuate wrinkles and pouchy eyes and something of their general facial expressions. The idea was to accentuate age and therefore wisdom, which was highly valued in ancient Rome.

|

| Hoff, "Portrait of a Roman Matron," digital, 2019 |

|

| Hoff, "Nero, after a Roman bust," digital 2019 |

|

| Hoff, "Unknown roman," after a Roman bust, 2019 |

The final drawing in this post was made from a Roman republican portrait bust. The subject is not known, so far as I could determine, but he must have been a wealthy patrician. He had a lean face and a determined, almost skeptical expression. In many of these, as here, I added irises, which were painted on. These were all very likely polychromed with paint that has worn away over the centuries. Adding irises makes these old old faces come alive.

For anyone "doin' the dailies"--a daily sketch or painting or whatever--these busts of the ancient wealthy and powerful are a rich source of material.

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

The Art of Euan Uglow

|

| Euan Uglow, "Self Portrait," oil on card, ca 1960 |

|

| Euan Uglow, "Woman in a White Skirt," oil on canvas, 1954 |

|

| Euan Uglow, "Girl in the South of France," oil on canvas, 1961 |

|

| Euan Uglow "Salt Triangle at Hyeres France," oil on canas, 1961 |

| |

| "Nude from 12 Regular Vertical Positions" |

During his later years Mr. Uglow's work became more and more analytical. An example is "Nude from Twelve Regular Vertical Positions from the Eye," a life-sized figure painted over a year and a half. Mr. Uglow's approach in this work was to build a platform more than six feet tall for the model, then he marked off divisions on the back at six inch intervals. He painted the figure from bottom to top while sitting on a purpose-built scaffold that was raised with each step upward so that his eyes were at the same level as each of the succeeding divisions. Mr. Uglow later said that he was attempting to reduce the visual distortion he had introduced in previous works. This barrel distortion he had introduced inadvertently by staying too close, so in this work he adjusted both distance from the model and height of his eyes. The result is a strangely elongated and unusual figure whose legs and torso don't quite match and yet somehow holds together. This particular work won prizes and sparked much discussion, mostly about the technique rather than the figure, a discussion deplored by Mr. Uglow, who commented that the figure was the subject, not the method.

|

| Euan Uglow, "Zagi," oil on canvas, 1981 |

These few works are only indicative of the oeuvre Mr. Uglow left behind. For those with an interest, there is a video on YouTube of his painting process, made in 1976, that provides much of interest and repays the time spent.

Friday, November 15, 2019

Fall on Druid Hill Creek

Although it is late November, the past few days before this post have felt more like December. The autumn colors have shriveled into brown and the leaves are crisp and sere. Unlike some years, a cold snap finished the season with a few inches of snow.

Early in the season, the trees held their leaves and stayed green. In fact, so little changed that even in early October (right) the trees were dense with foliage and the undergrowth of honeysuckle and small plants remained dense. This watercolor was done on the bank, using the same simple technique of pencil drawing, spotting in color emphasizing with ink and then finished with detail. The ink emphasis was confined to the center of interest. I used broad washes of color to explore light slanting into the woods.

The next small watercolor (left) is another done a little more than a week later, from nearly the same place on the bank. In this painting a tree that I had edited out of the first watercolor (above) shows up almost wrapping itself around the much taller mulberry while a thin black walnut seedling stands nearby. The same dense undergrowth and greenery show how little the season had advanced by then. There was virtually no color but greens in the woods and foliage across the creek from the studio.

But within only a few days the colors of autumn began. First to come are usually yellows--they would have been ash trees here in years past but the ashes have been cut down to stop emerald borers from advancing. Nonetheless, the other yellow trees fill in beautifully with flashes of yellow flame. Then come the reds in all of their abundance, from dark red-brown through rusty to glowing incandescent reds. Here in the upper Midwest this is the glory of fall.

About two weeks after the two watercolor sketches above I spent about ninety minutes along a street not far away, trying to catch some of the fall colors in paint. These trees presented a kind of stair step progression that made for a tall, narrow format (two pages in my sketchbook). The air was brisk and the sky crisp and clear, so the crispy brown leaves of the giant at the back made a great contrast to the smaller, brighter trees along the street. The light was autumnal and even though it was early afternoon, trees out of sight cast long shadows across the street. In only two weeks, this much change had come to this part of the country.

But the season had more in store, as I mentioned above. Last weekend we had a low temperature near zero degree Fahrenheit and two or three inches of snow. Since then the cold has finished the colors. This watercolor shows how the landscape turned drab, the snow accumulated along the dark-flowing creek, and the undergrowth here and there stayed a bit green despite the frigid blast. But that was the end of the color show, and effectively the end of Fall.

No doubt we will have some Indian summer before actual winter. I'm counting on it for a few more outdoor sessions.

---

Related Post

Changing Seasons

|

| "The Opposite Bank," watercolor 5x9, 10/8/19 |

|

| "Companions," watercolor, 5x9, 10/16/19 |

But within only a few days the colors of autumn began. First to come are usually yellows--they would have been ash trees here in years past but the ashes have been cut down to stop emerald borers from advancing. Nonetheless, the other yellow trees fill in beautifully with flashes of yellow flame. Then come the reds in all of their abundance, from dark red-brown through rusty to glowing incandescent reds. Here in the upper Midwest this is the glory of fall.

|

| "Color on Waterbury," 5x18, 11/2/19 |

|

| "Early Snow," watercolor, 5x9, 11/11/19 |

No doubt we will have some Indian summer before actual winter. I'm counting on it for a few more outdoor sessions.

---

Related Post

Changing Seasons

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Favorite Artists 10 - Hokusai

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) remains an enormous presence the world of art. His work in woodblock printing (a Japanese art known as ukiyo-e) was immensely popular in the closed Japanese society he lived in, selling huge volumes of prints as series, as individual items, and as books. He worked steadily and productively from his youth to nearly ninety and is said to have lamented in his last years that if he could only be given more time he would eventually learn to draw. After Japan opened to the West in the mid-19th century, prints and books of ukiyo-e by Hokusai and is fellow masters trickled into Europe, where Japonism, the rage for Japanese arts and culture, influenced entire movements, from Impressionists like Mary Cassatt to Post-Impressionists including Gauguin and Lautrec, to incorporate flat planes of color and strong outlining into oil paintings and prints.\

Hokusai himself was an unusual person. He changed his name perhaps thirty times, many more than the usual custom of the times. The first name we know him by describes the part of Edo where he was born, and the second means "North Light Studio," a neat allusion to his work. He was related in some way to a craftsman working for the Shogun, and so had access to excellent education and the upper classes of Japan, which doubtless was helpful to him. After working in several areas he eventually learned block cutting and became apprenticed to Katsukawa Shunshō a master of ukiyo-e whose work focused on courtesans and actors in kabuki. He worked there several years (and changed his name to Shunro), then in other studios until establishing his own. Ever restless, he moved more than ninety times in his life, reportedly because he never cleaned and simply walked away when his quarters became to dirty and cluttered. But through all of those moves he produced enormous amounts of work, including prints, drawings, and books. His most famous work is undoubtedly The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (above), one of his Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, which is still very popular in the West.

Favorite artists strike a chord, giving pleasure but challenging me, showing what can be done but requiring study to see how. Hokusai was a master of line, which translates into woodcuts easily, but more importantly despite his early upbringing in the Japanese upper classes he was a keen observer of the common people and their endlessly fascinating lives. My favorite of his works is the enormous, multivolume Manga (literally, sketches). These were enormously popular during Hokusai's lifetime and demonstrate his sympathy and love for peasants, vendors, sumo wrestlers, Buddhist monks, fishermen, courtesans, and all of the others. During the early 19th century, these sold briskly in multiple editions.

For those with more interest James Michener's Hokusai Sketchbooks is an excellent introduction. Michener compares Hokusai to the European Pieter Breughel, whose empathy toward the common people was similar. Michener comments that Hokusai's people are "tangled up in life," going about their daily affairs as he observes them with love. He shows us what men and women were like in those times in his place, Edo. Considering what we know of history, Hokusai's vision of the way people lived is a vibrant one. What wouldn't we would give for such drawings of Ancient Rome or Greece?

Because he had such a dedication to drawing (one of his best names translates as Old Man Mad About Drawing), his work presents formidable opportunities and challenges for the student. In his self portrait above for example, his treatment of the figure and the folds of the cloak are fascinating. They clearly depict the garments and posture well, yet are not quite in the traditions of the West. During the last few years I've tried my hand at copying some of these works both digitally and with pen and ink. A fairly famous work, "Saisoro," shows an actor doing a traditional, stylized Asian dance more than a thousand years old. In the dance a decrepit old man is gathering berries, his limbs weak, his gait halting. He dresses in white, and always has a basket a walking stick. The entire dance is a comment and lament on aging. I copied Hokusai's print and it's coloring using Sketchbook and a Wacom tablet.

Many pages of the Manga are devoted to street life. In the copy to the left, I took only a small corner of a much larger page and copied these two figures as they hurry through a rainstorm. The near figure is trudging along carrying rice in baskets while the far one, head down and hurrying, is trying to stay dry. Throughout the books we see these sorts of deceptively simple yet masterful drawings. There are pages of sumo wrestlers, workmen, geisha, bathers, fishermen, priests, archers, samurai, and more. Hokusai's interest and vision is wide and engaging and keeps changing from page to page of the Manga. Besides street scenes, Hokusai drew many landscapes, plants, animals, and fanciful creatures as well. He explored how the wind and water behave and the structures of the earth.

Perhaps the best known of Hokusai's work is the series Thirty-six View of Mount Fuji, released in 1831. In each, the sacred mountain is visible, looming over the countryside and the people. Fuji-san is Japan for many, representing the solidity and eternity. In these views, everything changes but Fuji is eternal (and by implication, so is Japan). The best known of these prints is The Great Wave but it is worthwhile to study all of them. One of my favorites is "Tsukada Island," with Mount Fuji in the far distance beyond the island and shore, boats plying the deep blue waters. There are actually thirty-eight views in this series of prints and most are superior.

Studying the art of the rest of the world is a useful way to alter one's viewpoint or perhaps change focus, as many Europeans did more than a century ago during the heyday of Japonism. Certainly copying Hokusai's drawings has been useful to me.

---

Previous in this series:

Favorite Artists

Favorite Artists 2--Chardin

Favorite Artists 3--Grant Wood

Favorite Artists 4--Diego Velazquez

Favorite Artists 5--Andrew Wyeth

Favorite Artists 6--Wayne Thiebaud

Favorite Artists 7 - Edward Hopper

Favorite Artists 8- Nicolai Fechin

Favorite Artists 9- Rembrandt

|

| Katsushika Hokusai, "The Great Wave Off Kanagawa, ukiyo-e, 1831 |

|

| Hokusai, "Self-portrait at 72" |

For those with more interest James Michener's Hokusai Sketchbooks is an excellent introduction. Michener compares Hokusai to the European Pieter Breughel, whose empathy toward the common people was similar. Michener comments that Hokusai's people are "tangled up in life," going about their daily affairs as he observes them with love. He shows us what men and women were like in those times in his place, Edo. Considering what we know of history, Hokusai's vision of the way people lived is a vibrant one. What wouldn't we would give for such drawings of Ancient Rome or Greece?

|

| Hoff, "Saisoro," digital, after Hokusai |

Many pages of the Manga are devoted to street life. In the copy to the left, I took only a small corner of a much larger page and copied these two figures as they hurry through a rainstorm. The near figure is trudging along carrying rice in baskets while the far one, head down and hurrying, is trying to stay dry. Throughout the books we see these sorts of deceptively simple yet masterful drawings. There are pages of sumo wrestlers, workmen, geisha, bathers, fishermen, priests, archers, samurai, and more. Hokusai's interest and vision is wide and engaging and keeps changing from page to page of the Manga. Besides street scenes, Hokusai drew many landscapes, plants, animals, and fanciful creatures as well. He explored how the wind and water behave and the structures of the earth.

Perhaps the best known of Hokusai's work is the series Thirty-six View of Mount Fuji, released in 1831. In each, the sacred mountain is visible, looming over the countryside and the people. Fuji-san is Japan for many, representing the solidity and eternity. In these views, everything changes but Fuji is eternal (and by implication, so is Japan). The best known of these prints is The Great Wave but it is worthwhile to study all of them. One of my favorites is "Tsukada Island," with Mount Fuji in the far distance beyond the island and shore, boats plying the deep blue waters. There are actually thirty-eight views in this series of prints and most are superior.

Studying the art of the rest of the world is a useful way to alter one's viewpoint or perhaps change focus, as many Europeans did more than a century ago during the heyday of Japonism. Certainly copying Hokusai's drawings has been useful to me.

---

Previous in this series:

Favorite Artists

Favorite Artists 2--Chardin

Favorite Artists 3--Grant Wood

Favorite Artists 4--Diego Velazquez

Favorite Artists 5--Andrew Wyeth

Favorite Artists 6--Wayne Thiebaud

Favorite Artists 7 - Edward Hopper

Favorite Artists 8- Nicolai Fechin

Favorite Artists 9- Rembrandt

Friday, November 08, 2019

Yellow

|

| Jean-Honore Fragonard, "Young Girl Reading," oil, 1776 |

Yellow falls between green and orange on the traditional color wheel, and it's complement is violet. In this color wheel, the primary colors are red, blue, and yellow and the secondary colors are green, orange, and violet. The range of hues from yellow to red-orange on the color wheel are warm in temperature and high in chroma, particularly yellow, whereas their complementary range of blue-green through violet are all considerably cooler and lower in chroma.

|

| Henri Regnault, "Salome," oil, 1870 |

Until relatively recently in human history, most yellows were dull, though the ancient pigment called orpiment (arsenic trisulfide) is a bright yellow and was used as far back as ancient Egypt. Orpiment was replaced, gradually, by lead-tin yellow (in the middle ages) and Naples yellow (another lead-based paint) in subsequent centuries. Other yellows available in the past have included Indian yellow, once said to have been made from the urine of cows fed only mango leaves but now made as synthetic pigment. None of those produced the high chroma yellows we have now. It was the introduction of chrome yellow and cadmium yellows and newer organic molecules that gave us the brilliant yellow colors in the late 19th century that became associated with vanGogh and the post-Impressionists.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, "Three Sunfowers," oil on canvas 1888 |

|

| Hoff, "Two Bottles," oil on panel, 6x8 |

|

| Hoff, "Winter Light," oil on panel, 6x8 |

---

Previous similar posts:

Red

Green

Blue

Tuesday, November 05, 2019

Inktober Finale

Inktober ended a few days ago and for me it was great for reviewing

and relearning ink techniques, and it was a lot of fun besides. At first

it was just something that sounded interesting but beginning to use

unforgiving ink again and daily was harder than I thought. But

gradually, over the course of more than thirty pen and ink drawings rust

begins to fall off.

These last drawings were probably the most enjoyable I've made. Each of them was done for a specific reason. The first one (left), was actually done outdoors on a sunny day when the leaves were still clinging. I was interested in how to show the foliage without being too picky about the drawing. Omitting detail helps when sketching, in my practice.

This cellist is a drawing based on a quick sketch. Sometimes when attending concerts I sketch the musicians, as I did in a concert a year or so ago. Using a scribbled ballpoint sketch for this particular drawing meant inventing some parts and reinforcing others. The cellist was engaged and enraptured by his instrument and the music, which was the feeling I was hoping to convey in doing this particular ink. I sat him sideways on his chair simply because it was an easier way to draw the image.

The next drawing is the head of an African lion. Drawing animals isn't something I do that much, so this particular picture was done for the practice in drawing big cats. They differ a great deal from the typical house cat--the nose is very broad, for one thing--so it isn't really possible to practice drawing one of these huge creatures from a tabby. The drawing style is a traditional one.

Bristlecone pines are the longest-living species on our planet, some surviving 5000 years or more. They're a wonderful subject to draw because of their twisted limbs and sparse foliage. They live in harsh high altitude environments, often rocky and dry. The wood tends to be fissured and riven, making interesting patterns for the artist. I drew this one from a reference photo I had, concentrating on the flowing patterns in the wood and neglecting everything else in the scene.

Finally, for the last drawing of Inktober 2019 I tackled a chicken. Chickens have been domesticated for thousands of years of course, but they always seem wild to me--they compete viciously with one another, scratch and scrabble in the chicken yard and try to peck little boys. Roosters like this one eye you with unhidden malice, simply waiting for a chance to take a little piece out of your hide. When I was a boy, my grandfather's rooster used to terrorize me, so perhaps that's where the look in this particular bird's glinting eye came from.

If you're interested in doing any kind of art--drawing, painting, whatever--my best advice to you is to do it regularly. Inktober was a good stimulus to draw with ink every day. There isn't really any trick to regular practice beside developing it as a habit.

---

Inktober Posts:

Inktober Plan

Another Shot of Ink(tober)

More Inktober

Halfway Through Inktober

An Inktober Update

These last drawings were probably the most enjoyable I've made. Each of them was done for a specific reason. The first one (left), was actually done outdoors on a sunny day when the leaves were still clinging. I was interested in how to show the foliage without being too picky about the drawing. Omitting detail helps when sketching, in my practice.

This cellist is a drawing based on a quick sketch. Sometimes when attending concerts I sketch the musicians, as I did in a concert a year or so ago. Using a scribbled ballpoint sketch for this particular drawing meant inventing some parts and reinforcing others. The cellist was engaged and enraptured by his instrument and the music, which was the feeling I was hoping to convey in doing this particular ink. I sat him sideways on his chair simply because it was an easier way to draw the image.

The next drawing is the head of an African lion. Drawing animals isn't something I do that much, so this particular picture was done for the practice in drawing big cats. They differ a great deal from the typical house cat--the nose is very broad, for one thing--so it isn't really possible to practice drawing one of these huge creatures from a tabby. The drawing style is a traditional one.

Bristlecone pines are the longest-living species on our planet, some surviving 5000 years or more. They're a wonderful subject to draw because of their twisted limbs and sparse foliage. They live in harsh high altitude environments, often rocky and dry. The wood tends to be fissured and riven, making interesting patterns for the artist. I drew this one from a reference photo I had, concentrating on the flowing patterns in the wood and neglecting everything else in the scene.

Finally, for the last drawing of Inktober 2019 I tackled a chicken. Chickens have been domesticated for thousands of years of course, but they always seem wild to me--they compete viciously with one another, scratch and scrabble in the chicken yard and try to peck little boys. Roosters like this one eye you with unhidden malice, simply waiting for a chance to take a little piece out of your hide. When I was a boy, my grandfather's rooster used to terrorize me, so perhaps that's where the look in this particular bird's glinting eye came from.

If you're interested in doing any kind of art--drawing, painting, whatever--my best advice to you is to do it regularly. Inktober was a good stimulus to draw with ink every day. There isn't really any trick to regular practice beside developing it as a habit.

Inktober Posts:

Inktober Plan

Another Shot of Ink(tober)

More Inktober

Halfway Through Inktober

An Inktober Update

Friday, November 01, 2019

Calaveras

In Mexico the Day of the Dead is actually a three day fiesta. On All Hallows Eve (our Halloween), children make altars and invite the spirits of dead children, or angelitos, for a visit. All Saints Day (November 1) is when adult spirits come to visit. The next day is All Souls Day, when families decorate the graves and tombs of their relatives. The fiesta is marked by celebrations, cardboard skeletons and decorations, avalanches of marigolds, special foods, and especially sugar skulls for children. Private altars are covered in offerings to the revered dead like favorite foods and beverages, photos, and memorabilia.

Unlike our own Halloween, which has become campy and based in horror films and fairy tales, the Day of the Dead is more rooted in family traditions, togetherness, and feasting and drinking. And also poking fun at pretense and pomp since we will all be bones one day. One of the important artistic traditions of the Day of the Dead is artistic representations of the skull or entire skeleton, known as calaveras.

|

| Jose Guadalupe Posada, "La Calavera Catrina," etching, ca. 1910 |

A wider definition of a calavera is any artistic representation, including literature, intended for the Day of the Dead. There have been many poems intended to gently criticize we living people and remind us of our mortality, for example. Drawings and paintings of skulls are obviously included as well. In Mexican tradition, calaveras are commonly full skeletons, usually represented as vain or wealthy or both. One of them, La Calavera Catrina, a character from the early 20th century, is particularly famous and has become the symbol of the Day of the Dead, at least in Mexico.

Since today is the Day of the Dead, here are some of my own calaveras in homage to the beloved deceased.

|

| Hoff, "Skull," graphite, 8x10 |

|

| Hoff, "Study for Vanitas," oil on canvas, 11x14 |

|

| Hoff, "Cubist Skull," oil on panel, 12x16 |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)