smile on the face of da Vinci's "La Gioconda," or "Mona Lisa." A tiny change in facial muscle position can alter a person's entire appearance. In the portrait by da Vinci, the smile is almost nonexistent, yet we recognize it as such. It's the very slight upturn of the woman's mouth and the neutral, level gaze that make us see her smiling.

|

| Rembrandt von Rijn, "Self Portrait"1659 |

In the same way, an expression conveying sorrow doesn't require much of a change in the face. Rembrandt painted himself with just such an expression in his "Self Portrait," 1659 (in the collection of the National Gallery in Washington). We see a man in late middle age with a subtle expression that conveys chronic sadness. At that time in his life Rembrandt was in serious straits, having been near bankruptcy in 1656. During the intervening several years before this portrait, he had sold all of his art and antiquities collection as well as his house and printing press. In short, he was nearly destitute, and it shows. In his expression I believe I see sharp intelligence and determination.

So it has occurred to me more often than once that learning to draw and paint human expressions is needful, and in particular adds layers of meaning to images of our fellow humans. These past few weeks I've been working a bit on facial expressions, drawing them using various media, including graphite, digital, and charcoal. In many cases I snagged an image of sadness, or pain, or other emotions from the internet. I also own "The Artist's Complete Guide to Facial Expression," by an artist named Gary Faigin, in print over 25 years now, and widely available. Faigin's discussion of how our facial muscles work to give us expression is a classic that I highly recommend.

|

| "Pain,"graphite, 5x7 |

|

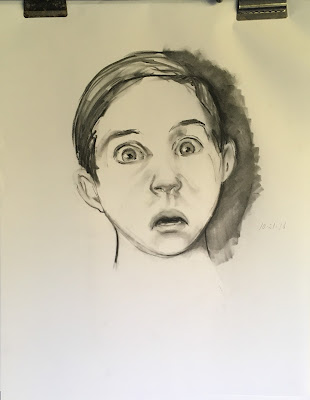

| "Fear," charcoal, 18x24 |

|

| "Sadness or anguish," graphite, 5x7 |

This sketch shows sadness or anguish. The eyes are clenched, the mouth is stretched tensely on a nearly horizontal line, and the chin is lifted and somewhat "puckered," showing tiny dimples and wrinkles.

Clearly, infusing emotion into portraits humanizes the sitter. Moreover, it provides layers of meaning that would otherwise be missed. In the final image below, Ilya Repin painted Ivan the Terrible holding his dying son after wounding and killing him in a fit of rage. Ivan looks terrified, completely undone by killing his own son. Without those eyes and the expression they contain Repin would have failed to convey just how horrible the act must have been. Further, Repin makes a comment on the dreadfulness of violence.

|

| Ilya Repin, "Ivan the Terrible and His Son," 1885 (detail) |

No comments:

Post a Comment